William McKinley

| William McKinley | |

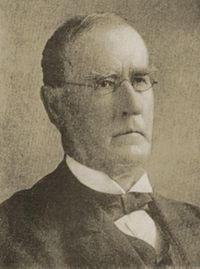

President William McKinley photographed by Courtney Art Studio, circa 1896. |

|

|

|

|

|---|---|

| In office March 4, 1897 – September 14, 1901 |

|

| Vice President | Garret A. Hobart (1897–1899) None (1899–1901) Theodore Roosevelt (1901) |

| Preceded by | Grover Cleveland |

| Succeeded by | Theodore Roosevelt |

|

39th Governor of Ohio

|

|

| In office January 11, 1892 – January 13, 1896 |

|

| Lieutenant | Andrew Lintner Harris |

| Preceded by | James E. Campbell |

| Succeeded by | Asa S. Bushnell |

|

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 17th, 16th, 18th, 20th congressional districts

|

|

| In office March 4, 1877- May 27, 1884, – March 4, 1887- March 3, 1891 |

|

|

|

|

| Born | January 29, 1843 Niles, Ohio |

| Died | September 14, 1901 (aged 58) Buffalo, New York |

| Birth name | William McKinley, Jr. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Ida Saxton McKinley |

| Children | Katherine, Ida |

| Alma mater | Allegheny College Albany Law School |

| Occupation | Lawyer |

| Religion | Methodist |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States of America Union |

| Service/branch | United States Army Union Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | Captain (brevet major) |

| Unit | 23rd Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

William McKinley, Jr. (January 29, 1843 – September 14, 1901) was the 25th President of the United States, and the last veteran of the American Civil War to be elected to that office. He was the last president to serve in the 19th century and the first to serve in the 20th.

By the 1880s, McKinley was a national Republican leader; his signature issue was high tariffs on imports as a formula for prosperity, as typified by his McKinley Tariff of 1890. As the Republican candidate in the 1896 presidential election, he upheld the gold standard, and promoted pluralism among ethnic groups. His campaign, designed by Mark Hanna, introduced new advertising-style campaign techniques that revolutionized campaign practices and beat back the crusading of his arch-rival, William Jennings Bryan. The 1896 election is often considered a realigning election that marked the beginning of the Progressive Era.

McKinley presided over a return to prosperity after the Panic of 1893, and made gold the base of the currency. He demanded that Spain end its atrocities in Cuba, which were outraging public opinion; Spain resisted the interference and the Spanish-American War became inevitable in 1898. The war was fast and easy, as the weak Spanish fleets were sunk and both Cuba and the Philippines were captured in 90 days. At the peace conference, McKinley agreed to purchase the former Spanish colonies of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, and set up a protectorate over Cuba. Although support for the war itself was widespread, the Democrats and anti-imperialists vehemently opposed the annexation of the Philippines, fearing a loss of republican values. McKinley also annexed the independent Republic of Hawaii and forced Hawaii to join the U.S., with all its residents becoming full American citizens. McKinley was reelected in the 1900 presidential election after another intense campaign versus Bryan, this one focused on foreign policy and the return of prosperity. After McKinley was assassinated by an anarchist, in 1901, he was succeeded by his Vice President Theodore Roosevelt, who continued McKinley's conservative policies.

Contents |

Early life

The McKinley clan arrived in Pennsylvania in the 1740s as part of a large migration of Scotch Irish. McKinley's grandfather David McKinley, after fighting in the American Revolution, moved to Ohio in the 1790s.

William McKinley, Jr., was born in Niles, Ohio, on January 29, 1843, the seventh of nine children. His parents, William Sr. (November 15, 1807 – November 24, 1892) and Nancy (Allison) McKinley (April 22, 1809 – December 12, 1897), were of Scots-Irish and English ancestry.[1] When McKinley was ten years old, he moved to Poland, Ohio.[2] He graduated from Poland Seminary and attended Mount Union College, where he was a member of the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity, then attended Allegheny College for one term in 1860. He did not take a degree.

In June 1861, at the start of the American Civil War, he enlisted in the Union Army, as a private in the 23rd Ohio Infantry. The regiment was sent to western Virginia, where it spent a year fighting small Confederate units. His superior officer, another future U.S. president, Rutherford B. Hayes, promoted McKinley to commissary sergeant for his bravery in battle. For driving a mule team delivering rations under enemy fire at Antietam, Hayes promoted him to Second Lieutenant. This pattern repeated several times during the war, and McKinley eventually mustered out as captain and brevet major of the same regiment in September 1865.

In 1869, the year he entered politics, McKinley met and began courting his future wife, Ida Saxton, marrying her two years later when she was 23 and he was 28. Within the first three years of their marriage the McKinleys would have two daughters, Katherine and Ida, but neither child lived to see the age of five.

Legal and early political career

McKinley attended Albany Law School in Albany, New York and was admitted to the bar in 1867. He practiced law in Canton, and served as prosecuting attorney of Stark County from 1869 to 1871. In June 1876, 33 striking miners in the employ of the industrialist Mark Hanna were imprisoned for rioting when Hanna brought in strikebreakers to do the work. McKinley defended the miners in court, and got all but one of them set free. When the miners came to McKinley to pay their legal fees, he refused to accept their money, which they had barely been able to raise. He first became active in the Republican party when he made "speeches in the Canton area for his old commander, Rutherford Hayes, then running for governor" in the state of Ohio.[3]

United States House of Representatives

With the help of Rutherford B. Hayes, McKinley was elected as a Republican to the United States House of Representatives for Ohio, and first served from 1877 to 1882, and second from 1885 to 1891. He was chairman of the Committee on Revision of the Laws from 1881 to 1883. He presented his credentials as a member-elect to the 48th Congress and served from March 4, 1883, until May 27, 1884. He was succeeded by Jonathan H. Wallace, who successfully contested his election. McKinley was again elected to the House of Representatives and served from March 4, 1885, to March 4, 1891. He was chairman of the Committee on Ways and Means from 1889 to 1891. In 1890 he wrote the McKinley Tariff, which raised rates to the highest in history, devastating the party in the off-year Democratic landslide of 1890. He lost his seat by the narrow margin of 300 votes, partly due to the unpopular tariff bill and partly due to gerrymandering.

Governor of Ohio

After leaving Congress, McKinley won the governorship of Ohio in 1891, defeating Democrat James E. Campbell; he was reelected in 1893 over Lawrence T. Neal. He was an unsuccessful presidential hopeful in 1892 but campaigned for the reelection of President Benjamin Harrison. As governor, he imposed an excise tax on corporations, secured safety legislation for transportation workers and restricted anti-union practices of employers.

In 1895 a community of severely impoverished miners in Hocking Valley telegraphed Governor McKinley to report their plight, writing, "Immediate relief needed." Within five hours McKinley had paid out of his own pocket for a railroad car full of food and other supplies to be sent to the miners. He then proceeded to contact the Chambers of Commerce in every major city in the state, instructing them to investigate the number of citizens living below poverty level. When reports returned revealing large numbers of starving Ohioans, the governor headed a charity drive and raised enough money to feed, clothe, and supply more than 10,000 people.

The 1896 election

Governor McKinley left office in early 1896 and, at the instigation of his friend Marcus Hanna, began actively campaigning for the Republican party's presidential nomination. After sweeping the 1894 congressional elections, Republican prospects appeared bright at the start of 1896. The Democratic Party was split on the issue of silver and many voters blamed the nation's economic woes on incumbent Grover Cleveland. McKinley's well-known expertise on the tariff issue, successful record as governor, and genial personality appealed to many Republican voters. His major opponent for the nomination, House Speaker Thomas B. Reed of Maine, had acquired too many enemies within the party over his political career and his supporters could not compete with Hanna's organization. After winning the nomination he went home and conducted his famous "front porch campaign", addressing hundreds of thousands of voters, including organizations ranging from traveling salesmen to bicycle clubs. Many of these voters campaigned for McKinley after returning home. Hanna, a wealthy industrialist, headed the McKinley campaign.

His opponent was William Jennings Bryan, who ran on a single issue of "free silver" and money policy. McKinley was against silver because it was a debased currency and overseas markets used gold, so it would harm foreign trade. McKinley promised that he would promote industry and banking, and guarantee prosperity for every group in a pluralistic nation. A Democratic cartoon ridiculed the promise, saying it would rock the boat. McKinley replied that the protective tariff would bring prosperity to all groups, city and country alike, while Bryan's free silver would create inflation but no new jobs, would bankrupt railroads, and would permanently damage the economy.

McKinley succeeded in getting votes from the urban areas and ethnic labor groups. Campaign manager Hanna raised $3.5 million from big business, and adopted newly-invented advertising techniques to spread McKinley's message.[4] Although Bryan had been ahead in August, McKinley's counter-crusade put him on the defensive and gigantic parades for McKinley in every major city a few days before the election undercut Bryan's allegations that workers were coerced to vote for McKinley. He defeated Bryan by a large margin. His appeal to all classes marked a realignment of American politics. His success in industrial cities gave the Republican party a grip on the North comparable to that of the Democrats in the South.

Presidency 1897–1901

Domestic policies

McKinley's inauguration marked the beginning of the greatest movement of consolidation that American business had ever seen.[5] Such consolidation of business (what was back then called trusts) was the culmination of a trend already far under way when McKinley took office. The administration did not actively use the Sherman Anti-trust act as would Theodore Roosevelt and therefore trusts were allowed to grow.

McKinley validated his claim as the "advance agent of prosperity" when the year 1897 brought a revival of business, agriculture, and general prosperity. This was due to the end of the Panic of 1893 which was caused by deflation dating back to the Civil War and underconsumption.[6] The end of the deflationary period was largely due to the Gold Standard Act of 1900 which set the value of the dollar, thus alleviating some of the monetary concerns that had plagued the United States since the 1870s.[7] This wave of prosperity, bolstered by US victory in the Spanish-American War, would carry on into the 20th century until the Panic of 1907 and ensured McKinley's reelection in 1900.

On June 16, 1897, a treaty was signed annexing the Republic of Hawaii to the United States. The Government of Hawaii speedily ratified this, but it lacked the necessary two-thirds vote in the U.S. Senate. The solution was to annex Hawaii by joint resolution. The resolution provided for the assumption by the United States of the Hawaiian debt up to $4,000,000. The Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) was extended to the islands, and Chinese immigration from Hawaii to the mainland was prohibited. The joint resolution passed on July 6, 1898, a majority of the Democrats with several Republicans, among these Speaker Reed, opposing. Shelby M. Cullom, John T. Morgan, Robert R. Hitt, Sanford B. Dole, and Walter F. Frear, made commissioners by its authority, drafted a territorial form of government, which became law April 30, 1900.

In Civil Service administration, McKinley reformed the system to make it more flexible in critical areas. The Republican platform, adopted after President Cleveland's extension of the merit system, emphatically endorsed this, as did McKinley himself. Against extreme pressure, particularly in the Department of War, the President resisted until May 29, 1899. His order of that date withdrew from the classified service 4,000 or more positions, removed 3,500 from the class theretofore filled through competitive examination or an orderly practice of promotion, and placed 6,416 more under a system drafted by the Secretary of War. The order declared regular a large number of temporary appointments made without examination, besides rendering eligible, as emergency appointees without examination, thousands who had served during the Spanish War.

Republicans pointed to the deficit under the Wilson Law with much the same concern manifested by President Grover Cleveland in 1888 over the surplus. A new tariff law had to be passed, if possible before a new Congressional election. An extra session of Congress was therefore summoned for March 15, 1897. The Ways and Means Committee, which had been at work for three months, forthwith reported through Chairman Nelson Dingley the bill which bore his name. With equal promptness the Committee on Rules brought in a rule at once adopted by the House, whereby the new bill, in spite of Democratic pleas for time to examine, discuss, and propose amendments, reached the Senate the last day of March. More deliberation marked procedure in the Senate. This body passed the bill after toning up its schedules with some 870 amendments, most of which pleased the Conference Committee and became law. The act was signed by the President July 24, 1897. The Dingley Act was estimated by its author to advance the average rate from the 40 percent of the Wilson Bill to approximately 50 percent, or a shade higher than the McKinley rate. As proportioned to consumption the tax imposed by it was probably heavier than that under either of its predecessors.

Reciprocity, a feature of the McKinley Tariff, was suspended by the Wilson Act. The Republican platform of 1896 declared protection and reciprocity twin measures of Republican policy. Clauses graced the Dingley Act allowing reciprocity treaties to be made, "duly ratified" by the Senate and "approved" by Congress. Under the third section of the Act some concessions were given and received, but the treaties negotiated under the fourth section, which involved lowering of strictly protective duties, met summary defeat when submitted to the Senate.

Foreign policies

McKinley hoped to make American producers supreme in world markets, and so his administration had a push for those foreign markets, which included the annexation of Hawaii and interests in China. While serving as a Congressman, McKinley had been an advocate for the annexation of Hawaii because he wanted to Americanize it and establish a naval base, but Senate resistance had previously proven insurmountable as domestic sugar producers and committed anti-expansionists stubbornly blocked any action. One notable observer of the time, Henry Adams, declared that the nation at this time was ruled by "McKinleyism", a "system of combinations, consolidations, and trusts realized at home and abroad." Although many of his diplomatic appointments went to political friends such as former Carnegie Steel president John George Alexander Leishman (minister to Switzerland and Turkey), professional diplomats such as Andrew Dickson White, John W. Foster, and John Hay also capably served. John Bassett Moore, the nation's leading scholar of international law, frequently advised the administration on the technical legal issues in its foreign relations.

Charges of cronyism emerged around his elevation of aging Ohio Senator John Sherman to head the State Department. While McKinley had hoped Sherman's reputation would bolster public perceptions of an otherwise lackluster Cabinet, Marcus Hanna's victory in the special election for the Ohio senate seat proved damaging to McKinley's reputation in some circles. Contrary to popular belief, McKinley had not selected Sherman to pave the way for Hanna. The president-elect had initially offered Hanna the largely honorific position of Postmaster General, which the Cleveland industrialist refused. McKinley's first choice for the State Department, Senator William Allison of Iowa, declined the offer. Sherman, who had previously served as Secretary of the Treasury, appeared a strong selection. Although Sherman was an experienced public servant, he was advanced in years and continually dodged rumors of advancing senility, charges that were not without merit. McKinley's longtime friend William Rufus Day operated as acting Secretary of State during the crucial months leading up to the Spanish-American War.

The Spanish-American War

The single event that came to define McKinley's presidency was the Spanish-American War. The conflict between the two countries grew from yellow journalist stories of Spanish atrocities in Cuba namely Spain's use of concentration camps and brutal force to quash the Cubans' rebellion. The Spanish repeatedly promised new reforms, then postponed them. Democrats and the sensationalist yellow journalism of William Randolph Hearst's newspapers pushed American public opinion against Spain through a 19th century media blitz for war. McKinley and the business community, aided by House Speaker Reed, opposed the growing public demand for war.[8][9] The McKinley Administration, however, was having trouble containing growing US sentiment.

To demonstrate growing American concern, a warship, the U.S.S. Maine, was dispatched to Havana harbor. On February 15, 1898, it mysteriously exploded and sank, causing the deaths of 260 men. No one was officially blamed but the episode riveted the nation. The uncertainty factor weakened McKinley and after more delays from Madrid he turned the matter over to Congress, which voted for war. Although the U.S. Army was poorly prepared, the Navy was ready and militia and national guard units rushed to the colors, most notably Theodore Roosevelt and his "Rough Riders". The naval war in Cuba and the Philippines was a success, the easiest war in U.S. history, and after 113 days, Spain agreed to peace terms at the Treaty of Paris in July. Secretary of State John Hay called it a "splendid little war." The United States gained ownership of Guam, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico, and temporary control over Cuba. Hawaii, which for years had tried to join the U.S., was annexed.[10]

At the Peace Conference Spain sold its rights to the Philippines to the U.S., which took control of the islands and suppressed local rebellions, over the objection of the Democrats and the newly formed Anti-Imperialist League. McKinley sent William Howard Taft to the Philippines and then to Rome to settle the long-standing dispute over lands owned by the Catholic Church. By 1901 the Philippines were peaceful again after a decade of turmoil.[10]

Civil rights

McKinley was the last Civil War veteran to be elected U.S. President, having served as a Major in the 23rd Ohio Regiment. He was raised a Methodist and an abolitionist by his mother in Poland, Ohio, and carried African American sympathies for their struggles under the "Jim Crow" laws throughout the nation while he was President. McKinley was unwilling to use federal power to enforce the 15th Amendment in the U.S. Constitution. During his Presidency there were many murders, torturings, and civil rights violations throughout the country against African Americans.[11]

McKinley was unwilling to return to the Reconstruction methods of the Congress after the Civil War during the Andrew Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant Administrations and did not take steps to ameliorate the effects of the 1896 U.S. Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson. In that decision the Supreme Court declared that public facilities that were "separate but equal" could be used to segregate African Americans from white society.

McKinley made several speeches on African American equality and justice:

| “ | It must not be equality and justice in the written law only. It must be equality and justice in the law's administration everywhere, and alike administered in every part of the Republic to every citizen thereof. It must not be the cold formality of constitutional enactment. It must be a living birthright.[12] | ” |

| “ | Our black allies must neither be forsaken nor deserted. I weigh my words. This is the great question not only of the present, but is the great question of the future; and this question will never be settled until it is settled upon principles of justice, recognizing the sanctity of the Constitution of the United States.[12] | ” |

| “ | Nothing can be permanently settled until the right of every citizen to participate equally in our State and National affairs is unalterably fixed. Tariff, finance, civil service, and all other political and party questions should remain open and unsettled until every citizen who has a constitutional right to share in the determination is free to enjoy it.[12] | ” |

Despite McKinley's laudatory rhetoric, the political realities prevented any real action on the part of his administration in regards to race relations. McKinley did little to alleviate the backwards situation of black Americans because he was "unwilling to alienate the white South."[7] The America of the 1890s, indeed, the America of the McKinley administration was frightfully racist. The period of the 1890s has been known to historians as the "nadir of race relations" as evidenced by the installment of Jim Crow laws and the decision of Plessy v. Ferguson. Despite his seeming inaction, however, McKinley did appoint thirty African-Americans to "positions of consequence" which was code for diplomatic and record office positions. During the Spanish-American War, McKinley even countermanded army orders preventing recruitment of African-American soldiers. Such efforts, as Gerald Bahles of the Miller Center of Public Affairs pointed out, however, did little to "stem the deteriorating position of blacks in American society."[13]

Election of 1900

McKinley was re-elected in 1900, this time with foreign policy paramount. Bryan had demanded war with Spain (and volunteered as a soldier), but strongly opposed annexation of the Philippines. He was also running on the same issue of free silver as he did before, but since the silver debate was ended with the passage of the Gold Standard Act of 1900, McKinley easily won re-election.

Second term

Mrs. McKinley's health was still poor after the 1900 campaign. She travelled to California with the President in May 1901, but became so ill in San Francisco that the planned tour of the Northwest was cancelled. The President spent most of his time with his wife; he was able to deliver a speech in San Jose on May 13 and to attend his parade in San Francisco on May 14.[14]

Significant events during presidency

- Panic of 1893 (an economic depression) ended (1897)

- Dingley Tariff (1897)

- Maximum Freight Case (1898)

- Annexation of Hawaii (1898)

- Spanish-American War (1898)

- Occupation of Cuba (1899–1902)

- Philippine-American War (1899–1902)

- Boxer Rebellion (1900)

- Gold Standard Act (1900)

Administration and cabinet

| The McKinley Cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

| President | William McKinley | 1897–1901 |

| Vice President | Garret A. Hobart | 1897–1899 |

| None | 1899–1901 | |

| Theodore Roosevelt | 1901 | |

| Secretary of State | John Sherman | 1897–1898 |

| William R. Day | 1898 | |

| John Hay | 1898–1901 | |

| Secretary of Treasury | Lyman J. Gage | 1897–1901 |

| Secretary of War | Russell A. Alger | 1897–1899 |

| Elihu Root | 1899–1901 | |

| Attorney General | Joseph McKenna | 1897–1898 |

| John W. Griggs | 1898–1901 | |

| Philander C. Knox | 1901 | |

| Postmaster General | James A. Gary | 1897–1898 |

| Charles E. Smith | 1898–1901 | |

| Secretary of the Navy | John D. Long | 1897–1901 |

| Secretary of the Interior | Cornelius N. Bliss | 1897–1899 |

| Ethan A. Hitchcock | 1899–1901 | |

| Secretary of Agriculture | James Wilson | 1897–1901 |

Judicial appointments

Supreme Court

McKinley appointed the following Justice to the Supreme Court of the United States:

- Joseph McKenna–1898

Other judges

Along with his Supreme Court appointment, McKinley appointed six judges to the United States Courts of Appeals, and 28 judges to the United States district courts.

Assassination

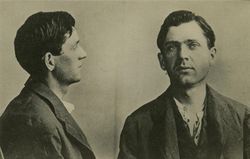

President and Mrs. McKinley attended the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. He delivered a speech about his positions on tariffs and foreign trade on September 5, 1901. The following morning, McKinley visited Niagara Falls before returning to the Exposition. That afternoon McKinley had an engagement to greet the public at the Temple of Music. Standing in line, Leon Frank Czolgosz waited with a pistol in his right hand concealed by a handkerchief. At 4:07 p.m. Czolgosz fired twice at the president. The first bullet grazed the president's shoulder. The second, however, went through McKinley's stomach, pancreas, and kidney, and finally lodged in the muscles of his back. The president whispered to his secretary, George Cortelyou “My wife, Cortelyou, be careful how you tell her, oh be careful.” Czolgosz would have fired again, but he was struck by a bystander and then subdued by an enraged crowd. The wounded McKinley even called out "Boys! Don't let them hurt him!"[15] because the angry crowd beat Czolgosz so severely it looked as if they might kill him on the spot.

One bullet was easily found and extracted, but doctors were unable to locate the second bullet. It was feared that the search for the bullet might cause more harm than good. In addition, McKinley appeared to be recovering, so doctors decided to leave the bullet where it was.[16]

The newly developed x-ray machine was displayed at the fair, but doctors were reluctant to use it on McKinley to search for the bullet because they did not know what side effects it might have on him. The operating room at the exposition's emergency hospital did not have any electric lighting, even though the exteriors of many of the buildings at the extravagant exposition were covered with thousands of light bulbs. The surgeons were unable to operate by candlelight because of the danger created by the flammable ether used to keep the president unconscious, so doctors were forced to use pans instead to reflect sunlight onto the operating table while they treated McKinley's wounds.

McKinley's doctors believed he would recover, and the President convalesced for more than a week in Buffalo at the home of the exposition's director. On the morning of September 12, he felt strong enough to receive his first food orally since the shooting—toast and a small cup of coffee.[17] However, by afternoon he began to experience discomfort and his condition rapidly worsened. McKinley began to go into shock. At 2:15 a.m. on September 14, 1901, eight days after he was shot, he died from gangrene surrounding his wounds.[18] He was 58. His last words were "It is God's way; His will be done, not ours."[19] He was originally buried in West Lawn Cemetery in Canton, Ohio, in the receiving vault. His remains were later reinterred in the McKinley Memorial, also in Canton.

Czolgosz was tried and found guilty of murder, and was executed by electric chair at Auburn Prison on October 29, 1901.

The scene of the assassination, the Temple of Music, was demolished in November 1901, along with the rest of the Exposition grounds. A stone marker in the middle of Fordham Drive, a residential street in Buffalo, marks the approximate spot where the shooting occurred. Czolgosz's revolver is on display in the Pan-American Exposition exhibit at the Buffalo and Erie County Historical Society in Buffalo.

"Temple of Music, Buffalo, N.Y. (Where Pres. McKinley was shot)," historical postcard. |

McKinley entering the Temple of Music shortly before his assassination. |

Leon Czolgosz shoots President McKinley with a concealed revolver. |

McKinley casket at Capitol. |

McKinley's coffin passing the Treasury building. |

Albumen print of the McKinley Memorial, shortly after its completion, ca. 1906–1915. |

Monuments and memorials

A funeral was held at the Milburn Mansion in Buffalo, after which the body was removed to Buffalo City Hall where it lay in-state for a public viewing. It was taken later to the White House, United States Capitol and finally to the late President's home in Canton for a memorial. Memorials for the President were held in London, England at Westminster Abbey and St Paul's Cathedral.[20][21]

- William McKinley Presidential Library and Museum, Canton, Ohio.

- McKinley Memorial Mausoleum, Canton, Ohio, his final resting place.

- National McKinley Birthplace Memorial Library and Museum, Niles, Ohio, designed by McKim, Mead and White, dedicated October 5, 1917.[22]

- McKinley Birthplace Home and Research Center, Niles, Ohio, a reconstruction on the site where he was born.

- The statue of McKinley in Muskegon, Ohio is believed to be the first raised in his honor in the country, put in place on May 23, 1902.[23] It was sculpted by Charles Henry Niehaus.

- At Bluff Point, near Plattsburgh, New York, a small monument topped with a memorial urn was erected following the assassination at the site of a large pine tree, known locally as the "McKinley Pine." Beneath this tree, the President would often relax while summering at the nearby Hotel Champlain. One year after the assassination, the tree was struck by lightning and destroyed. Little remains of the monument today.

- McKinley Classical Junior Academy, middle school in St. Louis, Missouri.

- McKinley Monument, Buffalo, New York.

- McKinley Monument, Springfield, Massachusetts.

- McKinley Monument, Scranton, Pennsylvania.

- McKinley Statue, Adams, Massachusetts.

- William McKinley Monument, San Francisco, California

- McKinley County, New Mexico is named in his honor.

- Mount McKinley, Alaska is named after him. (See Denali naming dispute.)

- McKinley Statue, Arcata, California.

- McKinleyville, California.

- McKinley, Maine.

- McKinley Statue, Dayton-Montgomery County Public Library, Dayton, Ohio.

- McKinley Statue, Walden, New York.

- McKinley Park, Chicago, Illinois

- McKinley Memorial, Redlands, California commemorates visit by the President.

- McKinley Monument, Antietam Battlefield, Maryland.

- McKinley Statue, Lucas County Courthouse Toledo, Ohio.

- McKinley Monument, Columbus, Ohio on the grounds of the Statehouse McKinley worked in as Ohio's Governor.

- McKinley Statue, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania outside Philadelphia City Hall.

- Calle McKinley (McKinley Street), Mayagüez, Puerto Rico.

- McKinley Vocational High School, Buffalo, New York.

- McKinley Technology High School, Washington, DC.

- McKinley Parkway, part of the Frederick Law Olmsted Park System of Buffalo, New York.

- McKinley Mall, Blasdell, New York (Southtown of Erie County, New York).

- William McKinley Junior High School, Bay Ridge, New York.

- McKinley Elementary Schools: Fairfield, Connecticut; Elgin, Illinois; Kenosha, Wisconsin; Toledo, Ohio; Marion, Ohio; Lakewood, Ohio; Fort Gratiot, Michigan; Port Huron, Michigan; Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan; Casper, Wyoming; Bakersfield, California; Corona, California; Redlands, California; Beaverton, Oregon; Arlington, VA; Abington Township, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania; Parkersburg, West Virginia; Erie, Pennsylvania; York, Pennsylvania;North Bergen, NJ Wyandotte, Michigan; Tacoma, Washington; Cadillac, Michigan; and Poland, Ohio.

- McKinley High Schools: Washington, D.C.; Honolulu, Hawaii; Canton, Ohio; Niles, Ohio; Sebring, Ohio; Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Saint Louis, Missouri (now McKinley Middle Classical Leadership Academy).

- McKinley Middle Schools:Racine, Wisconsin; Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Kenosha, Wisconsin; Cedar Rapids, Iowa; and Albuquerque, NM.

- McKinley Street, Waynesburg, OH.

- McKinley Street, Dearborn, MI.

- McKinley Avenue, Tacoma, WA.

- McKinley Street. Omaha, NE.

- McKinley's, a cafeteria in the Campus Center building at Allegheny College in Meadville, Pennsylvania, where President McKinley briefly attended as an undergraduate student.

- The $500 bill featured a portrait of William McKinley.

- McKinley Park in Soudan, Minnesota: a state park and campground named in his honor.

- Obelisk that was created to honor a visit from McKinley in Tower, Minnesota.

- McKinley Mezzanine: Albany Law School of Union University, Albany, NY.

- McKinley Neighborhood, Minneapolis, Minnesota

Media

William McKinley was the first President to appear on film extensively. His inauguration was also the first Presidential inauguration to be filmed. Most of the films were recorded by the Edison Company.

Disputed quotation

In 1903, an elderly supporter named James F. Rusling recalled that in 1899, McKinley had said to a religious delegation:

| “ | The truth is I didn't want the Philippines, and when they came to us as a gift from the gods, I did not know what to do with them... I sought counsel from all sides - Democrats as well as Republicans - but got little help. I thought first we would take only Manila; then Luzon; then other islands, perhaps, also. I walked the floor of the White House night after night until midnight; and I am not ashamed to tell you, gentlemen, that I went down on my knees and prayed to Almighty God for light and guidance more than one night. And one night late it came to me this way - I don't know how it was, but it came: (1) That we could not give them back to Spain - that would be cowardly and dishonorable; (2) that we could not turn them over to France or Germany - our commercial rivals in the Orient - that would be bad business and discreditable; (3) that we could not leave them to themselves - they were unfit for self-government - and they would soon have anarchy and misrule over there worse than Spain's was; and (4) that there was nothing left for us to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them, and by God's grace do the very best we could by them, as our fellow men for whom Christ also died. And then I went to bed and went to sleep and slept soundly. | ” |

The question is whether McKinley said any such thing as is italicized in point #4, especially regarding "Christianize" the natives, or whether Rusling added it. McKinley was a religious person but no on other observer or reporter heard McKinley say God told him to do anything. McKinley never used the term "Christianize" (and indeed it was rarely used by anyone in 1898). McKinley operated a highly effective publicity bureau in the White House and he gave hundreds of interviews to reporters, and hundreds of public speeches to promote his Philippines policy. Yet no authentic speech or newspaper report contains anything like the purported words or sentiment. The man who supposedly remembered it—an American Civil War veteran—had written a book on the war that was full of exaggeration. A highly specific quote from memory years after the event is unlikely enough—especially when the quote uses words like "Christianize" that were never used by McKinley. The conclusion of historians such as Lewis Gould is that, although it is possible this quote is legitimate (certainly McKinley expressed most of these sentiments generally), it is unlikely that he spoke these specific words, or that he said the uplift and civilize and Christianize them, part at all.[24]

See also

- History of the United States (1865-1918)

- List of assassinated American politicians

- List of Presidents of the United States

- U.S. presidential election, 1896

- U.S. presidential election, 1900

- U.S. Presidents on U.S. postage stamps

Notes

- ↑ RootsWeb's WorldConnect Project: McKinley Family.

- ↑ "William McKinley". Ohio Fundamental Documents. Ohio Historical Society. http://www.ohiohistory.org/onlinedoc/ohgovernment/governors/mckinley.html. Retrieved 2009-02-28.

- ↑ "William McKinley: 1892–1896". Ohio Governors, Ohio Historical Society. http://www.ohiohistory.org/onlinedoc/ohgovernment/governors/mckinley.html. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- ↑ Jensen (1971) ch 10

- ↑ Josephson, Matthew (1979 (reprint of 1840 version)). The President Makers. New York, New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons. pp. 9. ISBN 0-399-50387-0.

- ↑ Whitten, David. The Depression of 1893. Eh.net. 2010

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Bahles, Gerald. American President: William McKinley. Miller Center of Public Affairs. 2010

- ↑ Lewis Gould, The Spanish–American War and President McKinley (1982)

- ↑ Richard Hamilton, President McKinley, War, and Empire (2006)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Gould, The Spanish–American War and President McKinley (1982)

- ↑ LIB.oh.us

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 McKinley, William (1893). Speeches and addresses of William McKinley: from his election to Congress to the present time. D. Appleton and Company. http://books.google.com/?id=Qe5gk4hoJXAC.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ "Mrs. McKinley in a Critical Condition". The New York Times. May 16, 1901. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9405E4DB1030E132A25755C1A9639C946097D6CF. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- ↑ truTV.com

- ↑ "Biography of William McKinley". http://www.mckinley.lib.oh.us/McKinley/biography.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-04.

- ↑ William McKinley: Post-Shooting Medical Course at Medical History of American Presidents

- ↑ Rixey P. M., Mann M. D., Mynter H., Park R., Wasdin E., McBurney C., Stockton C. G.: The official report on the case of President McKinley. JAMA 1901; 37: 1029–1059.

- ↑ 1920 World Book, Volume VI, page 3575

- ↑ “The McKinley-Roosevelt Administration”, McKinleydeath.com.

- ↑ When Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom died on January 22, 1901, flags in the United States were lowered to half-mast in her honor by order of President William McKinley, one which was repaid by Britain when McKinley was assassinated later that year.

- ↑ LIB.oh.us

- ↑ "Monuments erected to McKinley throughout country". CantonRep.com. January 24, 2005. http://www.cantonrepository.com/index.php?Category=8&ID=204383&r=0. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- ↑ For a discussion of this question, see Gould (1980), pp. 140–142.

Further reading

Biographies

- Gould, Lewis L. "McKinley, William"; American National Biography Online (2000)

- Leech, Margaret. In the Days of McKinley. (1959), well-written biography

- Morgan, H. Wayne. William McKinley and His America. (1963). biography by scholar

- Olcott, Charles S. The Life of William McKinley. (1916), old official biography, online at Google

Domestic politics

- Faulkner, Harold U. Politics, Reform, and Expansion, 1890-1900 (1959). standard scholarly survey online edition

- Glad, Paul W. McKinley, Bryan, and the People (1964). short history of 1896 election

- Gould, Lewis L. The Presidency of William McKinley. (1981) the standard scholarly history

- Gould, Lewis L. The Spanish–American War and President McKinley (1982)

- Jensen, Richard. The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888-1896 (1971) why voters selected McKinley

- Jones, Stanley L. The Presidential Election of 1896. the standard history.

- Josephson, Matthew. The Politicos: 1865-1896 (1938) a leftist perspective

- Morgan, H. Wayne. From Hayes to McKinley: National Party Politics, 1877-1896 (1969), online edition

- Rhodes, James Ford. The McKinley and Roosevelt Administrations, 1897-1909 (1922), early scholarly history full text online

- Williams, R. Hal. Years of Decision: American Politics in the 1890s (1993) survey by scholar

Foreign policy

- Dobson, John M. Reticient Expansionism: The Foreign Policy of William McKinley. (1988).

- Fry Joseph A. "William McKinley and the Coming of the Spanish-American War: A Study of the Besmirching and Redemption of an Historical Image," Diplomatic History 3 (Winter 1979): 77-97

- Hamilton, Richard. President McKinley, War, and Empire (2006).

- Harrington, Fred H. "The Anti-Imperialist Movement in the United States, 1898-1900," Mississippi Valley Historical Review, Vol. 22, No. 2 (Sept. 1935), pp. 211–230 in JSTOR

- Holbo, Paul S. "Presidential Leadership in Foreign Affairs: William McKinley and the Turpie-Foraker Amendment," The American Historical Review 1967 72 (4): 1321-1335. in JSTOR

- May, Ernest. Imperial Democracy: The Emergence of America as a Great Power (1961)

- Offner, John L. "McKinley and the Spanish-American War," Presidential Studies Quarterly Vol. 34#1 (2004) pp 50+. online edition

- Offner, John L. An Unwanted War: The Diplomacy of the United States and Spain over Cuba, 1895-1898 (1992) online edition

- Paterson. Thomas G. "United States Intervention in Cuba, 1898: Interpretations of the Spanish-American-Cuban-Filipino War," The History Teacher, Vol. 29, No. 3 (May, 1996), pp. 341–361 in JSTOR

- Trask, David. The War with Spain in 1898. (1981).

Yearbooks

- Appletons' annual cyclopaedia and register of important events...1900 (1901), elaborate compendium of data and some primary sources online edition

Primary sources

- McKinley, William. Abraham Lincoln. An Address by William McKinley of Ohio. Before the Marquette Club. Chicago. February 12, 1896(1896)

- McKinley, William. Speeches and Addresses of William McKinley: from his election to Congress to the present time (1893)

- McKinley, William. Speeches and Addresses of William McKinley: from March 1, 1897, to May 30, 1900 (1900)

- McKinley, William. The Tariff; a Review of the Tariff Legislation of the United States from 1812 to 1896 (1904)

External links

- William McKinley at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress Retrieved on 2008-10-19

- William McKinley: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress

- 1st State of the Union Address

- 2nd State of the Union Address

- 3rd State of the Union Address

- 4th State of the Union Address

- Assassination Site

- Audio clips of McKinley's speeches

- Biography of William McKinley

- Encyclopedia Americana: William McKinley

- First Inaugural Address

- Internet Public Library: William McKinley

- Library of Congress films of McKinley

- Presidential Biography by Stanley L. Klos

- Second Inaugural Address

- McKinley Assassination Ink: A Documentary History

- William McKinley Presidential Library and Memorial

- White House biography

- Works by William McKinley at Project Gutenberg

- Essay on William McKinley and shorter essays on each member of his cabinet and First Lady from the Miller Center of Public Affairs

- A film clip of William McKinley's inauguration is available for free download at the Internet Archive [more]

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Grover Cleveland |

President of the United States March 4, 1897–September 14, 1901 |

Succeeded by Theodore Roosevelt |

| Preceded by James E. Campbell |

Governor of Ohio January 11, 1892–January 13, 1896 |

Succeeded by Asa S. Bushnell |

| United States House of Representatives | ||

| Preceded by Isaac H. Taylor |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 18th congressional district March 4, 1887 – March 4, 1891 |

Succeeded by Joseph D. Taylor |

| Preceded by David R. Paige |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 20th congressional district March 4, 1885 – March 4, 1887 |

Succeeded by George W. Crouse |

| Preceded by Addison S. McClure |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 18th congressional district March 4, 1883 – March 4, 1885 |

Succeeded by Jonathan H. Wallace |

| Preceded by James Monroe |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 17th congressional district March 4, 1881 – March 4, 1883 |

Succeeded by Joseph D. Taylor |

| Preceded by Lorenzo Danford |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 16th congressional district March 4, 1879 – March 4, 1881 |

Succeeded by Jonathan T. Updegraff |

| Preceded by Laurin D. Woodworth |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Ohio's 17th congressional district March 4, 1877 – March 4, 1879 |

Succeeded by James Monroe |

| Preceded by Roger Q. Mills |

Chairman of the United States House Committee on Ways and Means 1889–1891 |

Succeeded by William M. Springer |

| Party political offices | ||

| Preceded by Benjamin Harrison |

Republican Party presidential candidate 1896, 1900 |

Succeeded by Theodore Roosevelt |

| Honorary titles | ||

| Preceded by John A. Logan |

Persons who have lain in state or honor in the United States Capitol rotunda September 17, 1901 |

Succeeded by Pierre Charles L'Enfant |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||